By Blair Hurley

My mother’s final gift to me was a pair of Ivanka Trump shoes.

The gift didn’t mean in 2012 what it meant in 2022. A decade ago, it was just a pair of pretty shoes, and the Trump name did not mean then what it does now, and she was dying. In our changed cultural moment, an era my mother never had the chance to know, I wonder how I can possibly keep these shoes—and how I can possibly let them go.

She’d been fighting cancer for nearly two years, through fearsome surgeries and round after round of scorch-the-earth chemo. By Christmas, there was nothing more to do, and she entered hospice care at home. By then I was twenty-four and living in Cambridge, traveling home to the suburbs of Boston on the train every day and sitting with her. My sister and I helped her sort through the beautiful sweaters she had knitted herself, or her impressive collection of jewelry. She loved finding clever ways to elevate an outfit or be the most sharply-dressed person in the room. At five-foot eleven in flats, she made an impression wherever she went, and she enjoyed the sharp eye required for fashion, the hunt for special, elegant pieces. She loved shoes and bought her favorite designers marked down on eBay. In her closet was a neat line of spiky or pointy or bold design choices, the right shoe for every occasion. I remember a midnight-blue dress, and a pair of black-and-white Chanel shoes with towering heels slender as wine glass stems, her long shapely legs striding across a dance floor in them, winning compliments and envious looks from the other women in the room.

I was her frumpy, bookish daughter who fought shoes and makeup and jewelry all through the teen years, and then looked around in my twenties and discovered I’d missed all the hundred small cues of femininity, elegance, and womanhood that she had been sending me. All along she’d been demonstrating how to match colors, iron a knife-edge pleat in a pair of slacks, accessorize an outfit with a chunky piece of jewelry, apply mascara in crisp upward strokes with a steady hand. I craved her sense of style, but didn’t see the years of study and practice and gradual acquiring of good taste that it required. When I went to a party or a poetry reading once I moved to New York, I dressed in the same jeans and crewneck sweaters as the men, and saw the other women around me in dresses and catlike leggings, the makeup around their eyes dramatic and exact. My mother knew I was struggling to belong. She made sure that every Christmas and birthday, she’d give me the stack of books I asked for, but also something I didn’t know to ask for—a pair of knee-high boots, some pearl earrings, a little black dress—so that I’d have something in my closet I could put on and feel good about.

By the time my birthday came in June, she was very ill. I don’t think she had left the house in some time, and it was difficult for her to get out of bed. But we had a little party anyway, just us and some close family friends. We laughed easily about small things. The summer heat beat in through the open door, and bugs flew in and out, and we didn’t notice or care. I made a cake from an old recipe belonging to my great-grandmother, the typewritten writing on the faded index card calling for a pound of butter, a pound of flour. When I served the cake, I watched my mother anxiously, waiting for her verdict. It still makes me laugh to remember that she didn’t mince words: “It’s a bit dry,” she announced. I could always trust that I’d get her honest opinion, on a piece of writing or anything else I gave her, hoping for her approval.

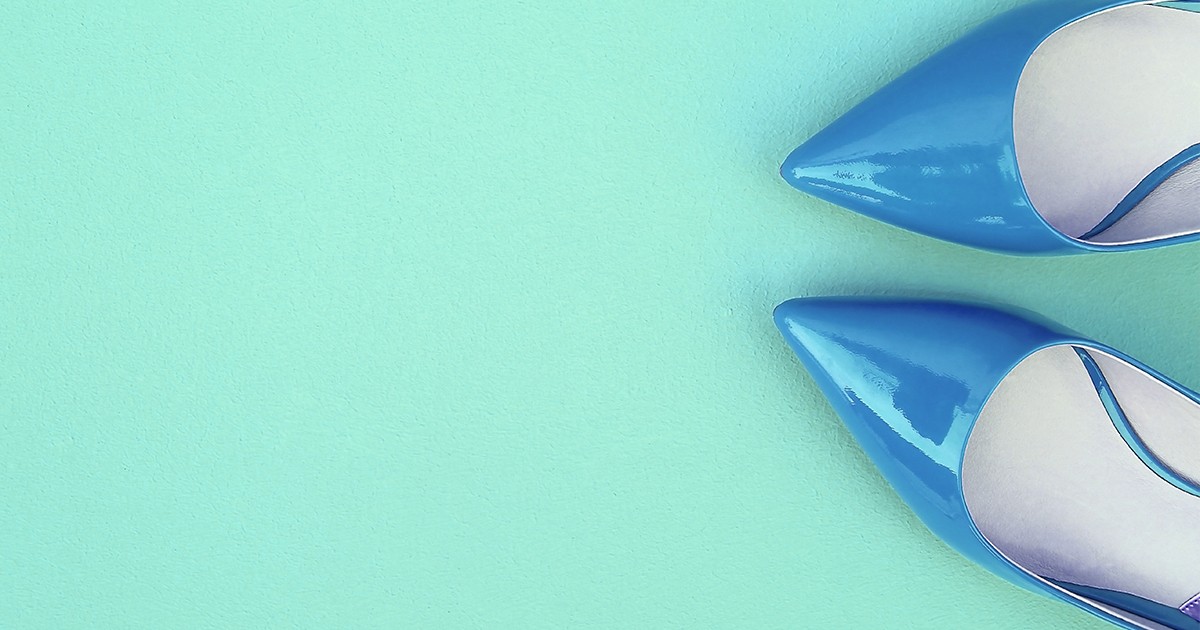

We salvaged the cake with ice cream. I remember all of us looking at her at the end of the table, wondering without saying if she was feeling good enough to be there with us that night. Several times I forgot what age I was supposed to be turning. I was trying to finish my novel and become a writer, but the words wouldn’t come that year. I remember the special quiet when my mother produced my present in her thin hands. I unwrapped it and saw a bright salmon-pink box, the Ivanka Trump logo. I opened the box and nestled among the tissue paper was a pair of bright-blue patent leather shoes. They were flats with a low vamp, which my mother insisted a shoe needed to look sexy, and they came to long, wicked points. The blue was a deep gem tone, like a Caribbean Sea. They were beautiful shoes. I remember wondering how she had scrounged up the energy to search for the perfect shoes for me. I wore them to my sister’s wedding in September to match my blue bridesmaid dress, and stared down at them while my father gave a toast and asked us all to share a moment of silence, watching them blur in and out of focus as I blinked tears from my eyes.

The shoes are in their salmon-pink box in my closet now. I’ve carted them to three apartments and to a new country. I haven’t worn them since my sister’s wedding, though I’ve occasionally opened the box and looked at them and then put them back with a sigh. They’re beautiful shoes, exactly the kind I’d like to wear, though perhaps they make more of a statement than I’m capable of pulling off. Sometimes a pair of shoes is more than a pair of shoes. It has felt wrong to have them since sometime in 2014 or 2015, when the true implications of wearing Trump shoes became plain. The entire wannabe empire and its sneering contempt for large swaths of the human race is sickening. But I still can’t bear to give the shoes away, or toss them in the bin. I imagine there are many women out there with Ivanka Trump clothing or shoes in their closet; perhaps there are many stories like mine, of gifts given, treasured memories, now tainted. How do we learn to live with the changed knowledge of ourselves, of our culture, the wounded image of who we are? I know that we can never fully go back. Losing someone you love is like entering a strange country you never knew before. The finality of the crossing is what strikes me, again and again. The exile from her, her voice, her gentle hand on my head, is permanent.

Every now and then I open the box again. Like grief, I suppose, you can choose to box it up and put it away, and when you allow yourself to open it, the memory is there as fresh and painful as ever: the Irish Spring soap smell of her, the freckles under her eyes. Still as fresh as ever is the disbelief that she is gone. The leather still gleams, the shade of blue is still as bright and cerulean as the day I opened them and felt like her special girl, for whom she had worked to find a special gift—I looked up at her, the shoes before me in their tissue paper. All our faces harsh in the evening shadows of the dining room. The steep caverns that had been carved into her lovely face. I didn’t want to ruin the moment by saying too much. But sometimes a pair of shoes is more than a pair of shoes. She gave me the gift, and then it was late, she was tired. She went upstairs to bed. The rest of us were left at the dining table, smiling at old jokes, the mood quiet in the summer night. We didn’t look toward the darkened hall. We were learning what the dinner table would look and feel like without her. We were learning to live in that altered light.