By Wendy Brown

It was an old house, well over a hundred years. The majority of its three-story bulk hunkered over cornerstones on the edge of a steep hillside. I was in the basement where the solid walls ran the length of the back of the house with one door opening to the hill, which fell away to the White River below. From that height, the river seemed sleepy as it steadily snaked its course. When in school, kids would query, ‘you live in the big house, the mansion?’ It was a tolerant house, withstanding banshees setting jumps in doorways and galloping a circular course from the front through the living room, then dining room, kitchen, pantry, back hall and a charge to finish in the spacious front entry. It welcomed the punishing pounding of pogo sticks and an ever-changing menagerie of cats, guinea pigs, dogs, even a snake. It was a loving house with storytelling and poetry reading upon its hearth, “Little Orphan Annie came to our house to stay…”

Ahhh, it was a lovely house to grow up in. Sometimes dad called it a white elephant, or a reason we might go to the poor house. It was white clapboard and even had a widow’s walk crowning it’s third story. At Christmas, dad would string lights in the lookout that could be seen for miles.

The lights were not yet lit, for this was only the end of the Thanksgiving weekend. It was a typical grey, dank December day. But I was in an interior basement room with cream-colored concrete blocks, to the right of the flight of wide wooden steps that descended from the front hall.

Those stairs remind me of my only brother. The place where mom helped him pick ticks off his Boa constrictor, with no thought then that he would lose his life in the jungles of Vietnam. My brother, who would sit on those steps and play his guitar. The boards of those stairs had a song of their own. Not only did their risers literally squeak and creak but they bore witness to the generations the house had held, the house whose hidden passages seemed to suggest mysteries and the possibility of an underground railroad. It seemed to breathe and sigh with its knowledge of the joys and tribulations of many lives.

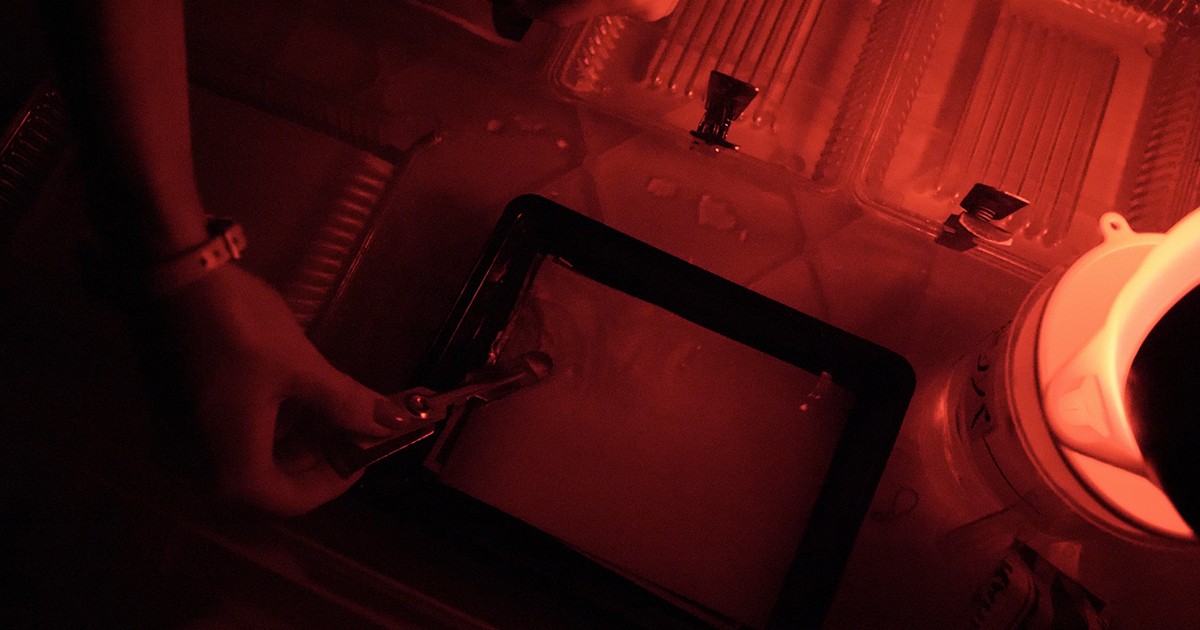

When I was accepted to graduate school, I quit my job to spend some time back home. Having grown up with parents who encouraged creativity, I had taken up photography. On that December day, I was trying to understand the enlarger on a work bench before me.

The room was narrow with casks of wine, in the making, at the far end. Wine making paraphernalia littered the shelves along with bags of powdered silt for pottery. The kiln and shelves of glazing compounds were in the next room over and dad’s woodworking shop on the far side of the stairs. The smell of sawdust and damp clay permeated the air. One of my sisters was driving back to South Carolina, and my baby sister was on a bus back to her college in Illinois. My eldest sister, Mary, was flying back to D.C. with her fiancé, James, whom the family had met over the Thanksgiving holiday. Mom and dad were above, probably in the kitchen snacking on Thanksgiving leftovers. After a weekend of boisterous family gatherings, I was immersed in solitude studying the sheet of negatives and trying to figure how to print them.

There was a faint jangle of the phone in the room above. Could I hear through the massive joists and thick hardwood planks of the old house’s floorboards? Or did I just imagine my mother’s gasp of air that escaped in a weak wail? It felt as if the house itself ushered me up the stairs for I did not hear my feet fall or feel the steps beneath me. A second more, to round a corner, and my parents’ embrace opened to pull me in.

To pull me into their grief of losing another child. There were no survivors on Flight #514.

Editor’s Note: TWA Flight #514 crashed on December 1, 1974, en route from Indianapolis and Columbus to Washington D.C. The author’s sister, Mary, was one of 92 people on board who died in the crash.