By Virginia Muzik

“Sometimes, I feel like a small, brown stain of a man,” you’d say in your low moments. At times whispered as an aside, your voice quiet in defeat, eyes not meeting mine. Or stated matter-of-factly, glaring at me, daring me to disagree.

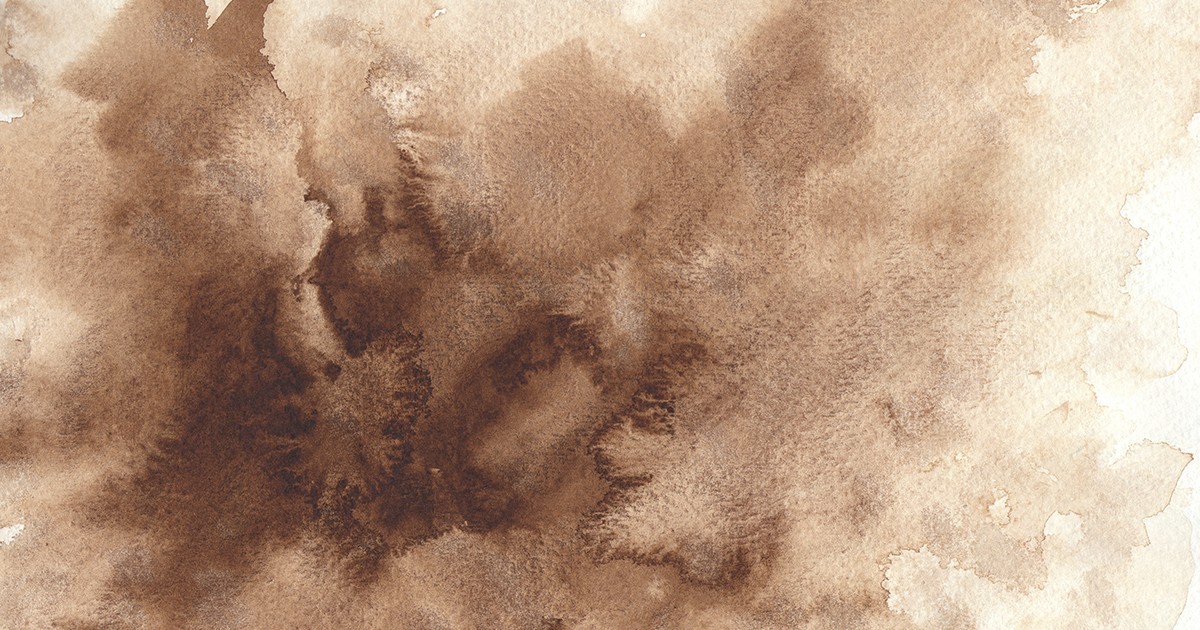

I’d wince at your words, unsure where to put them, but knowing my words wouldn’t help. So, I’d say nothing, instead imagining what pesky small, brown stains of shame look like, the ones you tried rubbing out with booze. What oozing trauma looks like, seeping slowly, corroding your mind and your life.

***

One childhood moment set your path: innocence robbed by a relative’s act. But you said nothing of it back then, instead hurling your rage at me for decades; spitting caustic words, beating, berating, bullying. So, while I held you close in my heart, and ached for your approval, I had to keep my distance—to protect myself.

Years later, you told me your pain; as you self-medicated, still struggling to make your life work. But your neediness consumed me, as your trauma swallowed you. While you drank, I flinched at your every phone call and visit: What does he want now?

You’d shut yourself in for stretches. Benders. And once, when you hadn’t returned my texts or calls, I stopped by your apartment. Finding the front door ajar, I peered into the dark and you slurred, “Go away”. So I went away, cooing, “I love you,” helpless, heart breaking, thinking: Could it happen?

Then, it happened: two cops at our door four days before Christmas.

“Your brother’s body…found in his apartment…”

My body a lead weight sunk into the couch; mouth dry in horror. “How? When?”

“The coroner will determine the cause…we believe he’s been deceased at least six days.”

***

Many times since, I’ve imagined how you looked when they found what was left: How many small, brown stains comprised this man, my big brother? Macabre, I know, but grief taunts a ruminating mind like mine.

After trauma cleaners had done their best to erase your traces, I still saw remnants, reminders of you in your home; evidence of the way you had lived—and died:

Small, brown stains on a wall at your front door, where your head must have hit when you fell.

Small, brown stains marking clothes strewn on the floor; in kitchen cupboards, from rusted tins; on papers pulled from drawers, looking for your will.

***

“I’m not staying,” you had said, on your last visit to me, early December. If only I’d known you meant it. If only you’d known.

You stepped up onto our porch then down again. Up, down, unsure if you were welcome, bracing for my “What now?” response.

But you said nothing of being in hospital weeks before, instead wanting iodine for a cut. I didn’t ask for details. That might have meant an expectation to invite you in.

Only since you died, when I trawled your medical records, searching, piecing together, I discovered that it was too late for iodine to fix the infection that put you in hospital. That you didn’t attend your post-discharge check-up. But even your medical notes were vague, leaving still so many questions.

Then, a man I never met decided how you died: “Undetermined natural causes”, the coroner wrote on your death certificate. Sometime between December 6, your last public sighting, and December 21, the day you were found.

Fifteen days to fade from your life—and mine.

***

You didn’t plan to leave, I know. Instead, you were undone by a perfect storm of childhood trauma, substance abuse, and self-neglect.

Now? My own small, brown stains remain: regret that I should have seen more, done more. Guilt over telling your secrets. Our secrets.

Now, as you drift further from me on the thinning threads of my grief, a thud of dread still slams my heart, breath catches in my chest when I picture my life without you; the person who knew me best, who hurt me most.

I’m free from our turmoil, yes, but I’m rudderless, because so much of me is because of you. Because of us. My therapist says I never gave up on you. I want to believe him. I try. With his coaxing, I’m learning to forgive myself, and you. Now, I’m working out who I am in your absence—it took losing my brother to find myself.