By Kathleen Melin

In snow-layered December, one month after my brain hemorrhage, I sat with my local family practitioner in her exam room—white chairs, white walls, gray exam table with a wide strip of white paper. Thankfully, she acted nonchalant about my skeletal thinness, dents from the burr holes on my forehead, and three-inch scars still bristling with stitches on my shaved crown. Thankfully, I was alive.

I’d returned home to my Wisconsin farm under the care of family, friends, and my country clinic after three weeks in a neurological critical care unit in Saint Paul, Minnesota. My children had dropped everything to be with me in the hospital, and now took turns staying with me at home. My daughter, on school break and spending Christmas with me, was grateful to be home for the holidays instead of my funeral since most people don’t survive a brain hemorrhage.

That day, she drove to the clinic on winter roads between open fields heaving with snow. Once there, she sized up the ice in the parking lot and pulled up beside the door. It was the third follow-up appointment that week.

“I’ll park and come in,” she said.

“I can do this one on my own,” I said.

“You’re sure?”

I wasn’t sure about much anymore, but I said, “I’ll be fine.”

Now, my family practitioner did the doctorly things and then asked, “Did you have an NDE?”

It took me a second to recognize the acronym: NDE—near-death experience.

“No—,” I said.

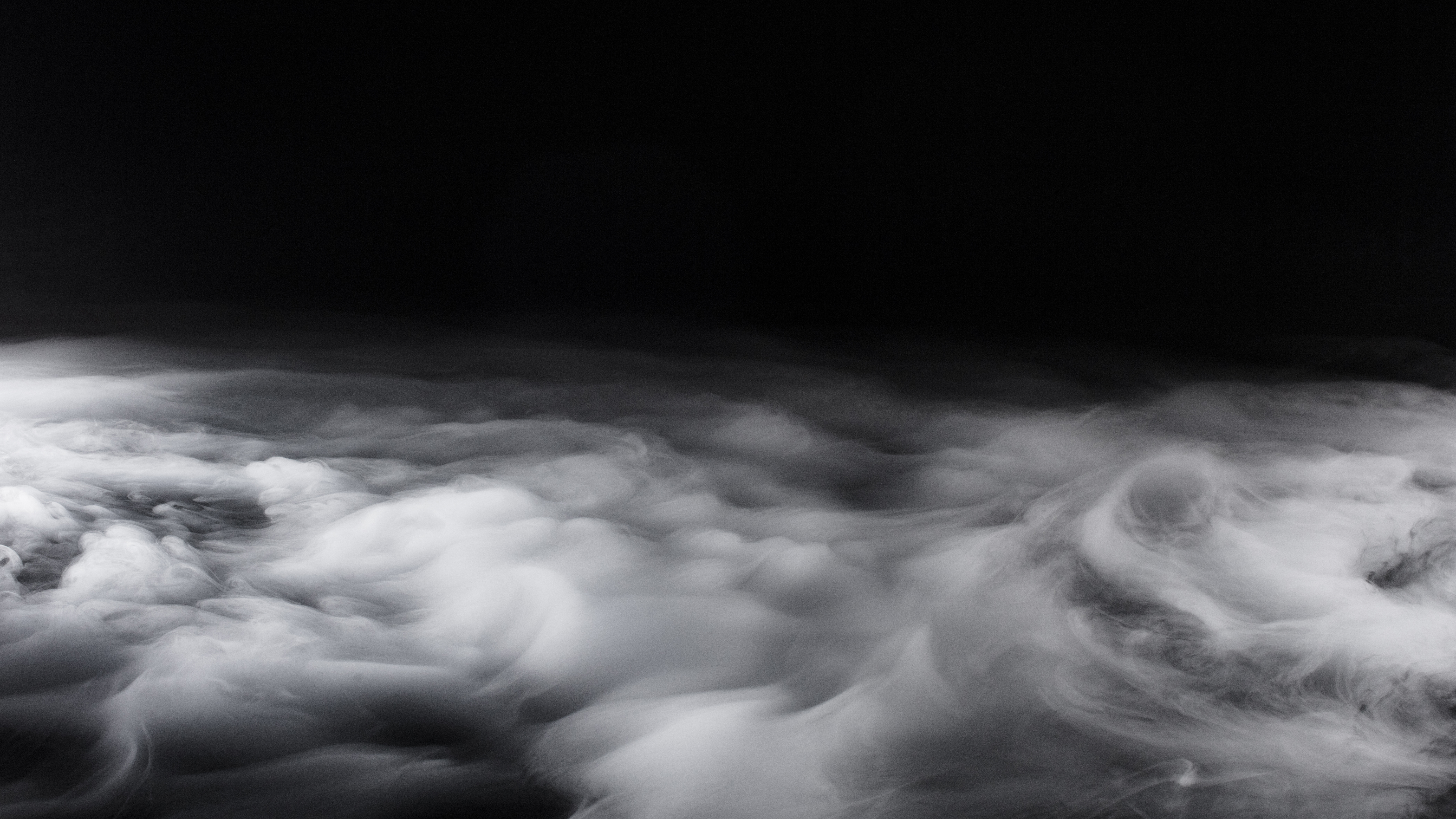

Still, I’d experienced something. For days, I lived inside layers of comforting silken gray that I couldn’t get through and didn’t want to. In that gray, I met the presence of those I came to call The Others, amorphous beings who, like a chorus, existed as a singular entity. They held me in the balm of an otherworldly vapor, though they never tangibly touched me. Still, I felt as if their hands cradled my head and shoulders. I sensed them smiling, as if lightly amused at my dire human circumstances.

“—but I did hear a voice,” I said.

“What did it say?”

“Not yet.”

Without comment, she looked away.

When she finished her protocols, she led me through narrow hallways to the lab. Afterwards, I wobbled on my own through the maze of white corridors. I circled and circled again, turned back, and did another revolution. There was a way out. I would find it.

I didn’t align my experience with an NDE as I understood it—going through a tunnel to a beautiful light, looking at my body from an outside vantage point, meeting deceased relatives, and doing a life review.

But I was and had been intrigued by mystic experiences and that interest started early.

The nursing home where my paternal grandfather lived his last breaths was across the street from my parents’ house. When I was seven years old, I’d skip across the street and read the Sunday comics to him. Early one January morning, my mother woke me and told me he had died during the night.

“I know,” I said. “He was already here and told me.”

A year later, my gentle maternal grandfather, a humble Swedish farmer, died at home. Shortly before his death, he had a stunning painful episode from which he recovered. “I was walking to a beautiful sunset,” he said. “I was almost there.” I imagined him reaching out his hand. “I just needed to take one more step.” He regretted not being able to do so.

In the month before my brain hemorrhage, I’d heard a woman speak on her NDE. She described being struck by lightning, living out of her body for seconds that felt much longer, and being met by her beloved grandfather. He told her she had to go back and when she did, she felt excruciating pain. Afterward, she had remarkable prescient abilities.

Now that’s an NDE, I thought.

My experience didn’t begin to compare.

Though fascinated by the mystical, I was also practical. I was aware of dissociation as a helpful survival skill when we’ve experienced deep trauma. Perhaps I had just been dissociating from the immense painful life-threatening event.

On top of that, I’d been dosed with all kinds of pharmaceuticals during my three weeks in the hospital. I wondered if my comforting sense of another world had been a drug-induced hallucination. I’d made a small sampling of recreational drugs in the 1970s, but none of it compared to the comforting oceanic gray in which I’d existed after the hemorrhage. Still, I couldn’t completely discount drugs as contributing to my mystic state.

Friends and acquaintances also asked if I’d had an NDE. I didn’t know. There was a transformative, comforting, peaceful “vision” and a reassuring voice. I did lose a sense of my physical body, but I didn’t view it from an outside vantage point. I did have a sublime change in my outlook. I was more alive to life, to beauty, and more at peace with inevitable challenges and sorrows. I’d experienced something, but I wasn’t sure what it was or what to call it.

Though NDEs are well-known in Western medicine, I couldn’t find anything in the research that helped me understand what I’d felt. My ethereal experience was a treasure and crossroads to me, but it didn’t compare to accounts by others. I resisted naming it an NDE. I couldn’t claim it as something it wasn’t.

Before the hemorrhage and mystic experience, I considered death a natural progression of life. I was curious about it. I liked the notion that I could be reunited with the souls of beloveds who’d gone before me. Still, I was in no hurry. It would come in its own time in its own way. But after the brain bleed, my feelings about death grounded in a deeper, more peaceful, almost enthusiastic anticipation. Generally, I didn’t talk about it.

But one day, I did.

Five years post-hemorrhage, my brother and I hiked a trail, had a picnic, chatted philosophically, and caught up on family.

“How are you doing?” he asked.

I gave my practiced answer: “Better than ever.”

I also acknowledged I was changed. When I told him my happy opinion that death would be good, he laughed mildly.

That day, as we said goodbye, I felt such tenderness for him and tenuousness about his life. Two days later, he ended up in the hospital with a life-threatening health event of his own. I didn’t identify my feelings as prescient, but they were.

The urgency of everyday life and the slippery, unbound experience of The Others both lived in my days. Something in human nature, at least my nature, wanted words and definitions, a way to communicate and interpret the experience of The Others. But it all seemed so wacky, woo-woo, and undefinable, even with my mystic leanings. Still, I continued searching for anything that would help me reconcile the mystic experience.

I was thrilled to come upon the work of researchers on the differences between a drug-induced hallucination and an NDE. While acknowledging some overlap, they concluded that an NDE remains distinctly in its own category. That assessment aligned with my experience and I accepted it readily.

Down the hoary trail I continued, stumbling here and there, dropping into the cold and getting up again, and then, the silver key appeared: The Near-Death Experience Scale.

Researchers worldwide have articulated and intricately discussed the range of characteristics of an NDE. From this, they’ve created a questionnaire with scaled answers to assess possible NDEs. I printed it out, sharpened a number two pencil, and began.

It categorized questions as cognitive, affective, paranormal, and/or transcendental. I could relate to the questions about experiencing changes in time, feelings of peace and harmony, existing beyond my body, and meeting a “presence.” But I had no awareness of things going on elsewhere. There had been no bright light. My senses were no more vivid than usual.

I scored slightly above the median for NDE and comfortably in the category of what researchers call a Near Death-Like Experience to account for those who have some, but not all and not the deepest level, of the phenomena. My mind relaxed.

Near Death-Like Experience—NDLE.

It allowed my mystic experience to be what it was, neither minimizing nor exaggerating it.

That day at the clinic, after swaying through the hallways, I did find my way to the door. I opened it to sharp fresh air and my daughter, who was waiting for me.