By Eve West Bessier

I will wear wool socks and a warm hat when I go under. The operating room is a meat locker.

The nurse gives me plastic bags to put over my socks to preserve the sterile environment.

My mother’s eyes are not their usual blue. We won’t know until after the surgery if the tumor is malignant.

The nurse inserts the IV needle into my vein, her icy fingers on my cold wrist. I want to talk to the surgeon again. I want to see her hands.

On the gurney, I watch the ceiling tiles go by like hopscotch squares. My feet lead through the swinging doors into the operating room. John Wayne in True Grit. The surgery is scheduled to take one hour and forty minutes, a feature length.

They roll the gurney up next to the operating table.

“On a count of three, we will lift you over,” they inform me.

The table is hard. I feel its cold steel through two blankets.

“Most folks like to be sedated before they arrive,” says the anesthesiologist.

I’m highly sensitive to drugs and didn’t want to add anything to the already heady dose of the anesthetic. I also wanted the anesthesiologist to give me a subliminal suggestion to have no nausea after the surgery, and that required I be conscious just prior to going under.

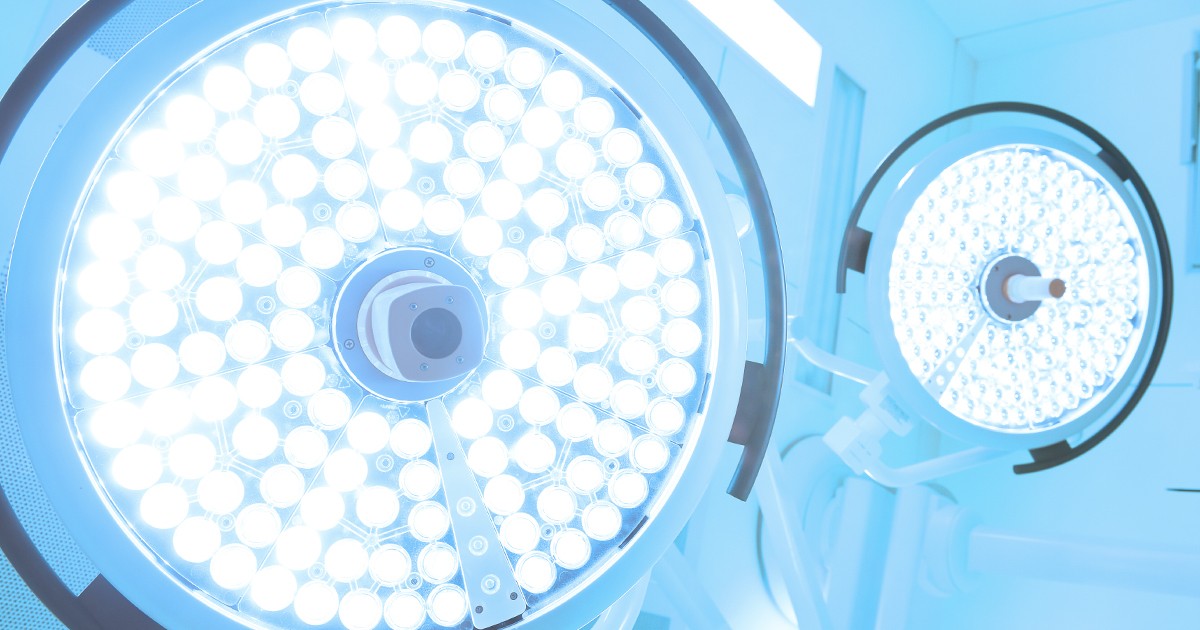

I contemplate the twin overhead lights, at least three feet in diameter each. Bright as truth. More light than I have ever seen in one electric place.

I hear the anesthesiologist’s voice, but only briefly. There is no fading to black slowly, only the mask and the instant loss of consciousness.

I am not supposed to be able to remember: the sterile wipe, the quick, efficient incision, seven inches wide. The red line following the knife tip. Editor’s ink, deleting an entire chapter. The severing of the lower abdominal muscles. I do not remember. Still, I was not really gone. My soul was on call.

During the surgery, my mother and my closest friend sit in the chilled waiting room. After the first two hours, there is no word, no update. Even after four hours, there are no compassionate reassurances from hospital staff. Bare walls. Mauve chairs. Hospital cafeteria coffee, ham and cheese sandwiches in plastic boxes. Nothing to do but pace and wait. Wait and pray.

The sweet, soft skin, the blood-pink flesh of abdomen and belly, stretched, rolled, clamped, restrained. The scarlet hem of the corporeal garment pulled away to reveal the throbbing mass of all that makes us human.

The surgeon’s trained fingers, sealed in latex, dig for the anomalous tissue. The blood flow is cut off with metal pinchers and modern drugs, yet oozes under the sucking sound of vacuum tubes.

“It was the most beautiful tumor I have ever seen,” the surgeon tells me, later.

Should I be proud?

“It was nonmalignant,” she says and smiles.

I am flooded with relief and gratitude.

It was growing for eight years, they speculate, attached to my cervix and the outer wall of my uterus. Six pounds, three ounces, a simple ultrasound would have revealed it, the size of a baby’s head. All those years, they had claimed that my constant pain and my inability to digest food was somehow all in my head. The tumor had wrapped itself around my intestines and filled the abdominal cavity.

Acupuncture, Chinese herbs, homeopathy, psychotherapy, Neural-organizational Technique, kinesiology, crystal healing, biofeedback, meditation. None of it prevented this. The going under the knife. Raw flesh sewn, stapled and taped. Eight and three-quarters of an inch, metal staples along the puffy incision of skin, across the maw of swollen abdomen.

Over four hours of scraping to extract that most beautiful tumor I have ever seen from the walls of my abdominal cavity. My uterus and cervix were too compromised and had to be removed as well, cut away and tossed in the biohazard bag, as I drifted in the ethereal halfway house of anesthesia.

I am thirty-seven and have not yet been pregnant. Now biological motherhood is no longer possible. My general practitioner later asks me if I am going to sue for malpractice. I don’t sue but, in retrospect, I really should have. I deserved some compensation for all of the unnecessary pain, suffering and loss. It will be too late to sue by the time I realize my mistake.

After the surgery, in the cold and drafty hospital room, I try to sleep. A nurse wakes me up to take a blood sample. She wakes me up to take my temperature. She wakes me up to check my pulse and blood pressure. He wakes me up. Time to eat something. He wakes me up. Time to do some breathing exercises into the blue tubes with the white balls.

I have to walk down the hospital corridor. Three times a day. Three times a night. Fifteen minutes, twenty yards, there and back, on the nurse’s arm, pushing my wheeled IV.

They wheel me on a gurney to X-ray. Christmas decorations are pinned to the ceiling tiles. I watch tin foil Santas, red and green paper bells and tinsel tassels go by overhead. I’m wearing my black and white jester’s cap. To be warm and to be there with bells on.

I’m so cold, in so much pain. The massive equipment looming over my body makes me tiny, vulnerable. The crosshairs of the X-ray camera, black ink mark on my belly over my left kidney.

“Breathe. Hold it. Breathe. Hold it. Breathe.” The tech says. I comply.

Inside, where the tender tissue was scraped, cut, bullied, pulled and torn for over four hours, cells vibrate like fire.

Alone in the hospital room, I look at the large clock over the door. Its white face is visible in the yellow glow of the morphine button. It’s 3 a.m. I thought hours had passed since the last time I looked at the clock, but it’s only been ten minutes. I slip away. I am a blue light hovering near the ceiling. I wonder if I am dying now. If this is how it’s going to be. It’s peaceful up here. I feel no pain. I’m too weak to hold on. I am looking for a ledge to curl my soul over.

This escape from the pain is blissful. I want to stay here, but I hear my own voice from a distance. I am singing quietly, Rawhide, Rawhide, Rawhide. The theme from that old western television show.

I am no longer the blue light. I am back in the pain, but I am laughing at my song choice. I do have a rawhide, inside and out. Humor once again saves me but laughing when you have an abdominal incision wound is excruciating.

I am too weak, too anemic. There was too much blood loss. I receive a transfusion. Dark maroon blood suspended in thick plastic. Dark, so dark, dripping slowly into my arm.

It’s not enough. I receive a second transfusion. The night nurse thinks it is likely her donated blood. Same blood type.

“If you crave chocolate or dream in Hungarian, then it’s my blood,” she says.

You can have friends or family donate blood in advance, in case you will need it. However, such donated blood is billed a surcharge per pint because it must be processed, tested and stored separately. There is no extra charge for hospital stock blood.

I have no idea how much the night nurse’s stock blood has cost, but it will save my life.

The day nurse combs the rat’s nests from my long hair with large, gentle hands. Patiently. Twenty minutes later, she braids the greasy strands.

“When your bowels move, you can go home,” she tells me.

I have to give ’em shit, so I can get out of here. It takes many more days.

On the way home in my friend’s pickup truck, every road bump makes me wince. When I walk through the front door of the house, everything starts to go black. I am caught by my friend’s steady hands.

For weeks my mother sleeps on the living room couch, near my downstairs bedroom. When I need to use the toilet, I ring a little bell. She comes to me then, in her deep-night stupor, her gray hair in tufts, her breath smelling of sleep. I can’t pee without her help, can’t get out of bed. She is my anchor and my elevator. Rolling over and sitting up knocks the breath out of me with pain. Standing rakes at my receding residue of courage.

After three months, I am able to walk around the block, slowly on my mom’s arm like an aged grandmother.

The pain is not gone. I keep calling the urologist’s office.

“The pain is in my left kidney,” I tell them. “It’s severe.”

They tell me the surgery was serious and it will take time to recover.

I am not recovering. I am tanking, approaching toxic shock. I keep calling the doctor office and they finally listen to me.

The warm, radioactive dye moves through my blood’s loop again. I will have five injected dye X-ray sessions in the space of three months. It never occurs to me to ask what happens to the radioactivity. What kind of half-life are we talking about?

The series of X-rays reveal the curse of scar tissue: a blocked left ureter.

“Sometimes you nick something,” the surgeon says. “There’s a lot of blood, a lot of tissue.” She pushes a lock of curly, blonde hair away from her forehead.

Surgery number two is billed as hopefully minor. General anesthetic but no hospital stay if the procedure is successful. They plan to insert a coat-hanger-sized, plastic tube with coiled ends into the urethra, move it up into the bladder and then attempt to push it through the blocked ureter. The tube will remain in place for six weeks. Its two coiled ends will rest in the kidney and bladder, to keep things clear until everything heals.

If this procedure is not successful, they will keep me sedated and go to plan B. They will make a six-inch incision across my abdomen, at a diagonal this time. They will then cut the ureter above the bladder, remove the blocked section, insert the blue plastic tube down through the urethra and up through the ureter into the left kidney. They will then sew the ureter back into the bladder in a slightly different location.

I won’t know until I come out of the anesthetic if they were able to clear the ureter by inserting an instrument through the urethra, or if they had to cut me open again. I have to hope for the best, yet be prepared for the worst.

I remember my conversation with the angels in the bowels of the night just after the first surgery. I told them that facing this would leave me with no more fear. I should never have said that! Even in that moment, the one remaining fear swelled insidious through my blood, riding ahead of the crest of morphine. I can never go through this again.

As I phase out of the anesthetic, the frowning face of the urologist swims above me.

“The ureter was too blocked,” he says, his voice sounding hollow. “We were unable to push the tube through. Too much scar tissue.”

I am barely conscious yet, still in the recovery room. All I remember is the pain and the shock of knowing I have to endure all of this again.

When I come more fully out of the anesthetic, I can feel that my left thigh is completely numb. The skin on my lower belly and left thigh is gray, blue, purple, yellow and something approaching green.

I tell the surgeon when he is in my hospital room about the numbness.

“Will it heal?” I ask him. “Will the feeling come back?”

The urologist pushes his thick black-rimmed glasses higher on the bridge of his nose, refracting light away from his eyes. “The nerve might only be bruised, or it might be more severely damaged. Maybe the sensation will return, maybe it won’t.”

How can he be so nonplussed about this?

The sensation eventually does return, but I still have a strange distant tingling. Months later, an entire muscle in my left calf slowly atrophies and disappears. Collateral damage.

I survived being under the big lights, but the blue light of my soul still feels on call.