By Jessica Gould

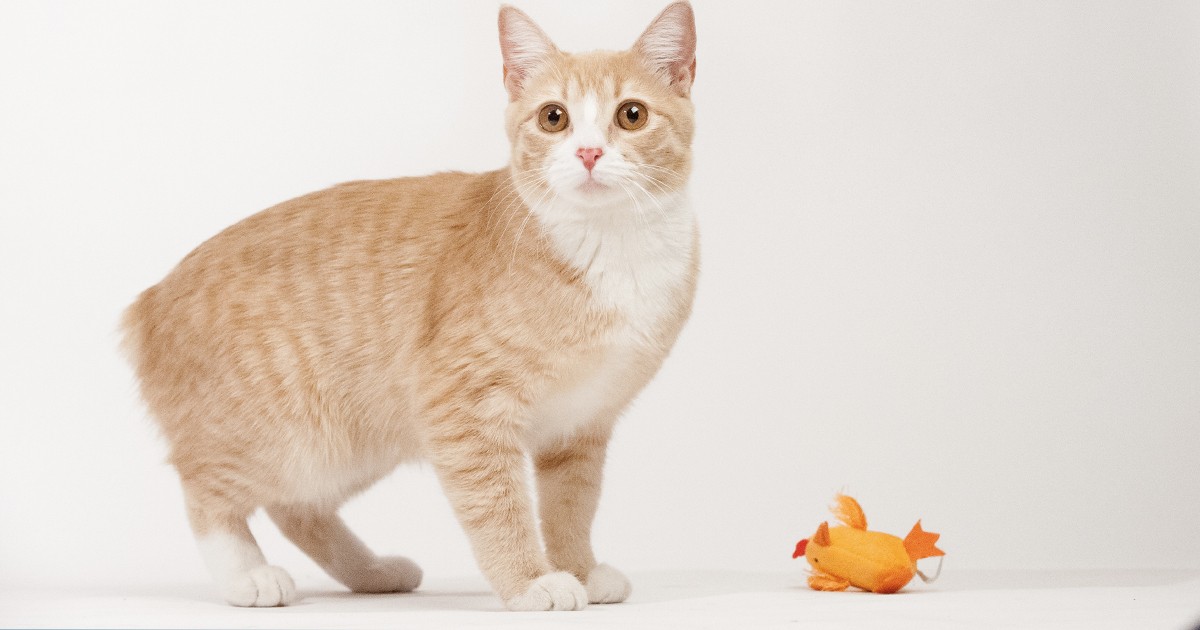

On a frigid November night fourteen years ago, a couple left their car in a dark alleyway on the Lower East Side for want of a parking space. When they returned from the evening’s activities, a clarion yelp issued from under the hood, causing them to hastily shut off the ignition. The large pair of golden eyes that greeted them upon peering inside belonged to an intrepid, buff-colored, grey-footed kitten, much aggrieved.

They bundled up the kitten and took him to a nearby bodega. Fortuitously called the Lucky Deli, the bodega was run by two Egyptians, who kindly took in the little one and named him Hamza. An outsize name for a pint-size being, Hamza (or Hamsa) in both Arabic and Hebrew means the number five. In the Koran, Hamza is also the name of the Uncle of Mohammad, called “Lion of Islam” for his bravery in battle. In Hebrew, the Hamza refers to the “eye of god,” which is visualized as an eye on an upside-down hand and is often worn as an amulet for protection.

Amused by the contrast of cuteness to import, I would later riff on the weighty name of this tiny feline. To Hamza, I added Ariel (for his sprite-like size and speed, also “Arie” means lion in Hebrew) Meshuggenah (a Yiddish word that perfectly captures the chaos of kitten behavior) Damien (which always suggested the demonic to me, another reference to kitten conduct), topped off by a “bin” before Gould, to indicate “son of” in the Arabic manner, in honor of Hamza Ariel Meshuggenah Damien bin Gould’s Egyptian rescuers.

The owners of the deli put out a towel on a shelf behind the counter for their furry new guest, who boldly ventured forth every day to greet customers in a voice of inverse proportion to his body size. Little Hamza quickly developed a following for his boldness, cuteness, and affectionate ways, always jumping in the lap of anyone who engaged him. For the rest of his life, he would loudly demand a towel for any lap upon which he landed.

The person who came to have him for the rest of his life was me. As the car lulled him to sleep in my lap on the way home, I made the mistake of talking. He stirred, registered a complaint, and reached up to put his paw over my mouth to shut me up. Arriving in his new home, he showed no signs of the usual cat-in-a-new-place fear, hiding precisely nowhere, having decided upon entry that everything there, including me, was his. He marched resolutely into my room, jumped on my bed, climbed over my supine body and up to my head, where he found my right earlobe and commenced to nurse on it, passing out in my hair afterwards.

The indignity of a bath at his first vet visit revealed the grey feet to be downy white and his age to be roughly four months. Subsequent vet visits, which became more frequent and urgent, revealed him to be a special needs kitty in precarious health. Countless late night cab rides to the Animal Hospital temporarily alleviated a condition for which some counseled surgery and others suggested euthanasia. I braced myself for the prospect of losing him before he reached the age of three.

Neither his commanding personality nor lion heart were cowed by a life-long health challenge, however, which eventually found relief with mini doses of human medicine thanks to the wisdom of a gifted Upper West Side vet with a small private practice. Many who met him and came to know him grew accustomed to his signature squillo. Many who loved him knew his loyalty, his astonishing recall of individual people, his abiding sweetness, startling intelligence, and human-like capacity for attachment.

For Hamza was a Manx, a tail-less breed of Viking and British origin that comes to us from the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. While any vestige of a British courtesy gene clearly took its leave long ago, Hamza’s marauder DNA roared loud and clear, and not just through his blond coloring.

He learned the difference between a casual and a business call, deciding that the latter required his input at all times. He learned how to stop me from working past a certain number of hours, by first shoveling the computer off my desk with his pink bubblegum nose, eventually economizing his energy by pushing the off button with his paw. He discovered that the best way to wake me up, in the event that standing on my head proved unfruitful, was to sweep all my jewelry to the floor, the resulting crash guaranteeing a swift exit from my bed. No meal of mine was safe from a noisy directive to return to my room to give him a cuddle. He lived by the rule that cuddle time was non-negotiable and that no project was so important that he would be deprived affection. Any closed door was viewed as a personal affront. He was so Velcro and deliciously cute that he got away with all of this, a sweet and gentle soul who, despite his myriad dictatorial commands, never scratched anyone out of malice.

To the surprise of many would-be cat surgeons, he made it past the age of three. Then he made it past five, then ten, then twelve, collecting admirers across the globe and indulging his lion spirit in the country, where he joyously scampered through the woods and personally supervised my lake swims, yelling at me to come in by 7 p.m. every evening. He somehow knew when the clock struck seven every single day and, because he was a cat, viewed water with the utmost circumspection.

This March, when the need to isolate became imperative, Hamza and I fled to the woodlands that I have known since infancy, where I learned how to swim before I could walk. He relished this transition, although after a while his nightly cuddle sessions changed to inexplicable retreats under the kitchen table. Nightly protests at the front door, also previously unthinkable, became common, accompanied by outright body slams and yells, as if he would die of pain unless let out.

One June day, while on my way to collect the mail, I spotted what looked like a grey and red dome-like shape in the road, as if a russet lichen encrusted tombstone had sprouted, mushroom-like, out of the earth. As I approached, I realized the strange form was a red-tailed hawk with its claws around a fresh kill. That it didn’t fly off at the sight of me filled me with both wonder and concern, and gave us the opportunity to lock eyes for an unusual length of time. I asked if its wings were ok and if I could come closer. Its penetrating gaze and a tip of the head said yes. After about ten minutes of this communion dressed up as a staring contest, the hawk took flight, soaring across the lake, squirrel dinner and all, and I had to content myself with its memory as no cell phone was at hand to document the uncanny encounter.

The indigenous population that inhabited the area before Europeans arrived were Algonquian. In Algonquian tradition, a soaring hawk is a sign of exhortation to leadership. A seated hawk sighting is interpreted as a harbinger of death.

Hamza’s nightly protests continued. I reluctantly gave in and he always came back shortly thereafter.

Until one night he didn’t.

I will never know exactly what happened to my sweet boy. Only that he went out after a couple of months of behaving strangely on and off, and at the age of fourteen, never came back. I want to think that the time of his departure from this life was his choice. It would be in keeping with his decisive personality and would offer me solace as I struggle with this overwhelming loss and the rage at the cosmic unfairness of his sudden and non-negotiable vanishing.

When in the thick of many a midnight Animal Hospital visit, I used to comfort myself with the thought that he was lucky he ended up with me, that someone else would have tired of the endless stress and expense of his care and would have given him up or given in to the calls to end his life prematurely.

But I was the lucky one. As mysteriously as he entered my life, he left it. Perhaps he spared us both suffering this way. I have no way of knowing. But I was fortunate indeed to have loved and been loved by such a strikingly human and endlessly loving being, a little buff-colored boy-kitten who formed a buffer between me and all that is wrong in the world, and I will always feel blessed that fate, serendipity, and perhaps Hamza himself conspired to make me his human.

And in a final flourish of his Viking-Irish DNA, he saved his ultimate feline vomit volley for the London Review of Books.