By Karen Storm

It’s dusk when the cab pulls up to my parents’ townhome in Mt. Clemens, Michigan. I pay the driver and pull my bag up the sidewalk. The screen door is unlocked. I walk in. Though it’s summer, I shuffle my feet on the mat. I stand overlooking the room. I don’t want to face what is here, my mother, dying. I don’t want to see what death looks like. I don’t want to see the hospital bed in the living room. My sister, Laurie, and stepfather, Don, stand together on one side of it, two people who rarely talk except to convey that they hate each other. They tell me to come in, to come over to the bed. I’m scared. I’m not ready to be so close to death.

Six hours earlier I left my husband, Gary, at the airport in Salt Lake City, the two of us standing by the escalator, holding each other and crying— oblivious to people, who, I realize now, were probably staring at us. We had not been apart since his diagnosis of terminal pancreatic cancer almost two months ago. He has cancer. My mother has cancer. My life has cancer. It’s that kind of a disease. Still, I can’t think about dying.

I walk over to my mother’s bed. She seems to be sleeping. I don’t want to awaken her, but I want her to know I am here. Then she reaches out her hand, and I take it.

Dry, slim, and warm; I’ve always admired her hands. It envelops mine, and I’m a small child again, walking to the bus with her. Her eyes stay closed. How strong her grip feels. Shouldn’t she be weak if she’s dying?

“We’ll talk tomorrow,” she breathes. I lay her hand back down.

Don called five days ago, saying the end was near. 41 I’d quickly made plans to be with her, in spite of Gary’s needs. He’d only been out of the hospital a couple of weeks. Gary’s sister, Mary, came to stay with him. They will talk, I know, and they need time alone together. She’s executor to his estate. I don’t care about estates. I care about Gary.

I turn away from my mother, sit on the couch, and look around the room. The light is dim, with only a glow from one of my mother’s treasured brass lamps near her bed. We sit quietly looking at Mom.

************

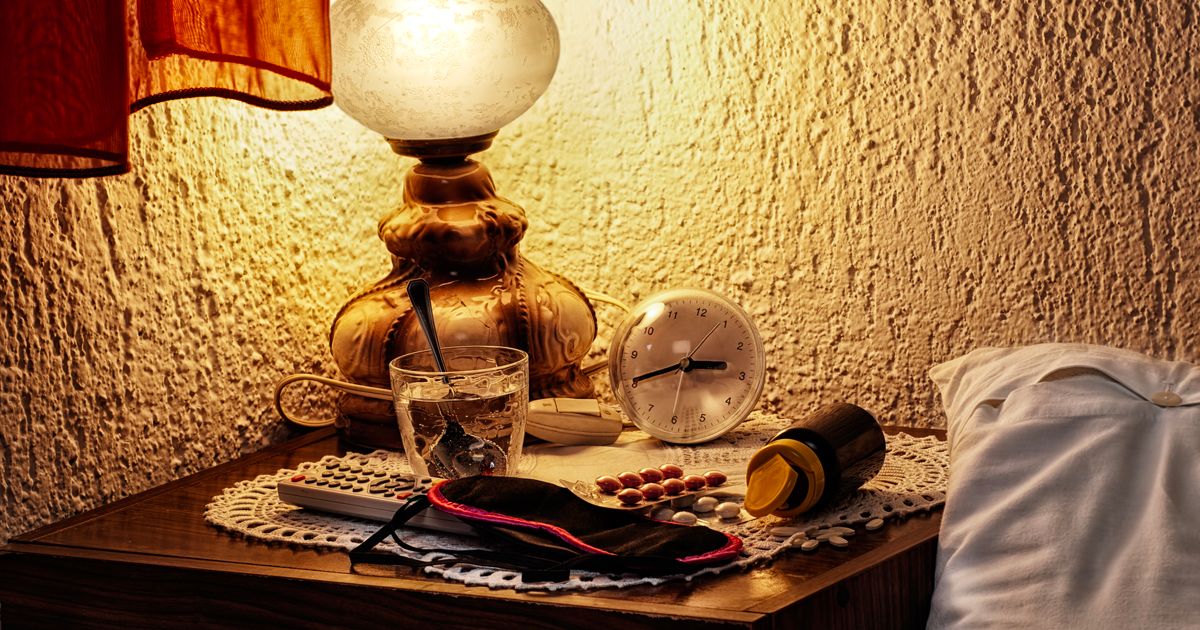

I was last here in March, before Gary’s diagnosis. Now, in early June, recalling that week feels like another world I once visited. I remember how Don had insisted that the drapes be closed, darkening the room, closing cancer in, but also shutting out the spring sunlight. Bottles of medicine spilled across the end tables where my mother’s cat knickknacks used to be. Don was in charge, but his uncertainty showed in the lists of what-to-do-when that he had taped to the walls. He had continued to teach at the community college so he was up and showered every day, but I sensed his stress by how his smoking had escalated. After years of smoking in the house, he no longer smoked around Mom, rather he’d gone outside again and again for one more cigarette.

My mother moaned from the bed much of that week. Sometimes she moaned before her next pain patch and pills when she was clearly suffering. Other times she moaned in confusion from the painkillers. What was hardest for me, though, was not the moaning but that when she was alert, she wanted to hash over her life. She was tortured by memories of things she believed she did poorly in her life. I was the daughter taking care of her—my two sisters and I had agreed to take turns one week at a time—thus it was my childhood for which she wanted absolution.

My mother married young, at seventeen, to a Norwegian immigrant, who worked on the Great Lakes fishing. Seven years into the marriage, she had three daughters, and he had a drinking problem. She divorced him shortly after World War II, leaving her with three girls to support, working days as a short order cook and nights as a bar waitress. Our grandparents took care of us during the day, but at night my sisters and I sat in a booth in the bar until we fell asleep. After work, she woke us up and walked us home to bed. Eventually she couldn’t keep us together. My sisters went to family to stay, and because I was the difficult child, I was put into Taylor Home, part orphanage, part home for troubled youth. Now, before dying, she wanted my forgiveness for that.

I dismissed her concerns, believing I had forgiven her. There was nothing to forgive; she did the best she could, and overall, as a mother, she had been about as good as most mothers and under great adversity. Yet I remembered being distant from her. I resisted her attempts at physical affection, I let her know she would never get close to me. But then she never persisted in trying to hug me; she let me pull away. I’ve often wondered how things might have been if she had held me tightly, insistent on her love. But there, in that living room where she was dying, I did not want to discuss these things. In that moment I preferred to call the past finished.

She told me, “I’m not ready to die. Not yet. I never did the things I wanted to do.” I wasn’t sure what this meant. It felt like regret, the sort of regret one reads about, the road not taken. I wonder what roads she might have taken, the poetry she loved to write. Maybe she wanted to write, like I do. She was 74 years old, young by today’s standards, but still, a respectable life span.

************

Laurie breaks my reflections, telling me that our other sister, Marylyn, will arrive the next day. Laurie’s been here for nearly a week. Laurie thrives on drama and unrest, and there’s a certain excitement in having our mother die, an excitement outside our usual lives. Will Laurie feed on that? How will I be when Gary dies—no, it’s too soon to think about Gary dying. Maybe he’ll be cured

Gosh, I feel tired. Flying from Salt Lake City to Minneapolis and then another flight to Detroit, losing a couple of hours along the way. Don reads my mind. “I’ve reserved rooms for you and Marylyn at the hotel on Gratiot. It’s close. You need some sleep.” He drives me to the hotel.

************

At the hotel, I can’t get the image of my mother in the bed out of my mind. That bed, surrounded by the paraphernalia of dying from cancer, drugs and swabs and mysterious paper packages to be opened by nurses, her pain patches. It all seemed to smother her, with only her head and face showing above the blanket tucked under her arms. Her once flowing dark curly hair, now sparse and stark white against her skeletal face. It’s as though dying like this, of cancer, strips away individuality, reducing my mother to a body. Is this how it will be for Gary?

Our house in Salt Lake City is already starting to look like a cancer house. Medicines and “remedies” friends have forced on us flow across our kitchen island. The bed’s been co-opted for resting after chemotherapy. There are pillows everywhere for Gary to prop his diminishing body against. I’ve bought him a recliner to sit in more comfortably. I hate them, but he loves them and ought to have what he loves if life is drawing short. So far, we’ve let the sunshine pour in; we crave the bright.

I can’t think about this. I don’t have to yet.

I get into bed. It’s eleven, but only nine Salt Lake time. I’m tired, but wide awake. I keep seeing my mother being swallowed by the hospital bed. I see Gary swallowed by the pillows. Somehow I manage to sleep.

************

Don calls early, waking me up. I eat the free hotel breakfast and by then he’s arrived to take me to the house. Marylyn has arrived from Florida. When I walk in, she is sitting next to Mom’s bed, holding her hand. The slight movement of Mom’s head suggests that she knows her oldest daughter, arguably the favorite, is there. I’ve not seen anyone die before. Is this how it goes, slowly, little by little? Will she say any last words? I’m ready to tell her I forgive her for putting me in the home, the words I couldn’t say when I visited in March.

But Mom never says a word. By evening she is in a coma. We sit by the bed, wiping her mouth with little sponges that look like suckers on a stick—suckers for the dying. I remember the suckers my children used to beg for when we went to the bank. Don and we three sisters talk about Mom during the day as she lies in the bed, her breathing getting raspy at times. It’s too much like a party. Is this how death goes or are we different? Don even orders a pizza. Yes, we must eat, but pizza feels festive. Gary’s death will not be festive. I will not allow it.

After eating, I want to clear my head. I go outside to walk around the neighborhood. The dusk is cool. A few children are out, doing wheelies off the curb. The curb doesn’t allow much of a leap, but still they laugh and do it over and over. Lights begin to turn on in houses. Outside is life as I remember it, busy, full of bustle, the winding down of a day. I’m not sure I appreciated that before, but I do now, as I walk back to the house.

South Pacific comes on the television, which we’ve had on all day in the background. Mom’s favorite Broadway show! We wheel the TV close—one last time, Mom—enjoy. I see her with my child’s eyes, cleaning the house singing “I’m gonna wash that man right outta my hair,” as she scrubs the grit and grime of her family.

By eleven pm, Marylyn and I are exhausted, so Don drives us back to the hotel. Laurie stays at the house, in my mother’s room, I assume. She and Don are still getting along, and I am grateful for that.

Once in the room I call Gary, it’s just after nine in Utah. On the phone, for a moment I pretend he’s my husband in another state, not my husband who has cancer and is probably dying. We make sweet small talk, like any married couple. Are your sisters there? Yes, Marylyn came this morning.

Did you and Mary do any driving around to show her Salt Lake City? Did you sleep well? I miss you.

I’ll be home as soon as I can. I love you.

I love you too.

I lay down for the night. This time my sleep is deep and dreamless. At about 7:30 my stepfather calls.

“She died about five am,” he tells me. “I’ve called Marylyn, but I haven’t called the mortuary yet. Laurie’s up. You and Marylyn should say goodbye before they take her away.”

Within the hour he arrives at the hotel to take us to see our mother. We walk into the living room. The curtains are drawn. She is in the bed where we left her last night, but now she is gray, like a stone. This body is not my mother.

Don wants to be composed, and he walks around the bed to the other side.

“I just held her and told her to let go—no more pain, it’ll be okay.” And suddenly he breaks down and cries, this alcoholic man that kept us wary throughout our childhoods with threats and punishments, cries. My sisters cry off and on through the morning. But I’m not a crier, not yet at least, and my mother and I were not as close as the two of them were to her. I can’t shake the feeling that I am an observer, someone watching a preview of a cancer death, and I don’t want this knowledge. I truly want to be here, fully in her death, but the urge to escape is strong. Run back to Utah, back to Gary. To rub out all the ways in which cancer has insinuated itself into our lives—remove the trappings of dying and bring back the life we were living.

A sheriff comes and takes the narcotic pain pills. Then the undertaker comes for the body, wrapping it in black plastic and wheeling it out. My mother is now a lump under a tarp. I cannot look. Will the authorities in Utah do these same things when— no if—Gary dies?

Later Jane and Walter, my children, arrive from Minneapolis. They arrive at the hotel in a huge car. Gary has arranged it all—their tickets and the car—he wants us to have the car to drive everyone around. I want to cry, but I don’t because I know the crying is for him and how amazing he is, how he knows exactly what I need—my children, my mom’s precious grandchildren, here with me to honor her and all that we have had with her in our lives— Grandma Marge, as they have always called her. I know that Gary feels death lurking around, coming for him as it’s come for my mother, but he stays in the realm of the living and knows exactly what I need and makes it happen.

In the week that follows, we have a small service and wake in her honor, and then it’s time to return to Salt Lake City.

All my life I’ve attended funerals as a detached observer. I attended physically but not emotionally. I used to attribute my reticence to a need for control. But it’s more than that. It’s awe and fear. Awe for how death closes the door to perfectly good lives with an agenda that might be delayed but can never be denied. Crying is what humans have but it seems an impotent expression to me.

In the past I’ve comforted myself with bits of poems: Death be not proud. . . one short sleep past, we wake eternally and death shall be no more. Or Approach thy grave like one who wraps the drapery of his couch about him, and lies down to pleasant dreams. But the closer I am to death, these poems, too, seem impotent. I’m seeing death anew, and it has my full attention, my awe and fear. I was inside in a room of death in Michigan, and a house of probable death awaits me in Utah. I fly home.